Find all related Progressive Post

Progressive Post

On March 17, the Dutch went to the polls in the middle of the Covid pandemic and a faltering roll-out of the vaccination programme. In addition, the government had resigned shortly before the elections over a scandal of racial profiling of families claiming child support. Neither the scandal nor the botched vaccination scheme seemed to hurt Prime Minister Rutte’s liberal VVD. He was riding high in the polls, resulting in a frequent media portrayal of Rutte as ‘the winner’ in this campaign.

Meanwhile, the ethnic-profiling scandal had resulted in the resignation of Lodewijk Asscher as leader of the Labour Party (PvdA), as he was considered responsible in the previous government for this policy. Thus, having lost already one of the main contenders on the left in the 2021 race, Rutte was also lucky enough that the minister of Health, responsible for the vaccinations, stepped down as leader of the Christian Democrats (CDA). Both PvdA and CDA had to find a new leader shortly before the elections, which is always an uphill battle for voters to get to know and trust the candidate.

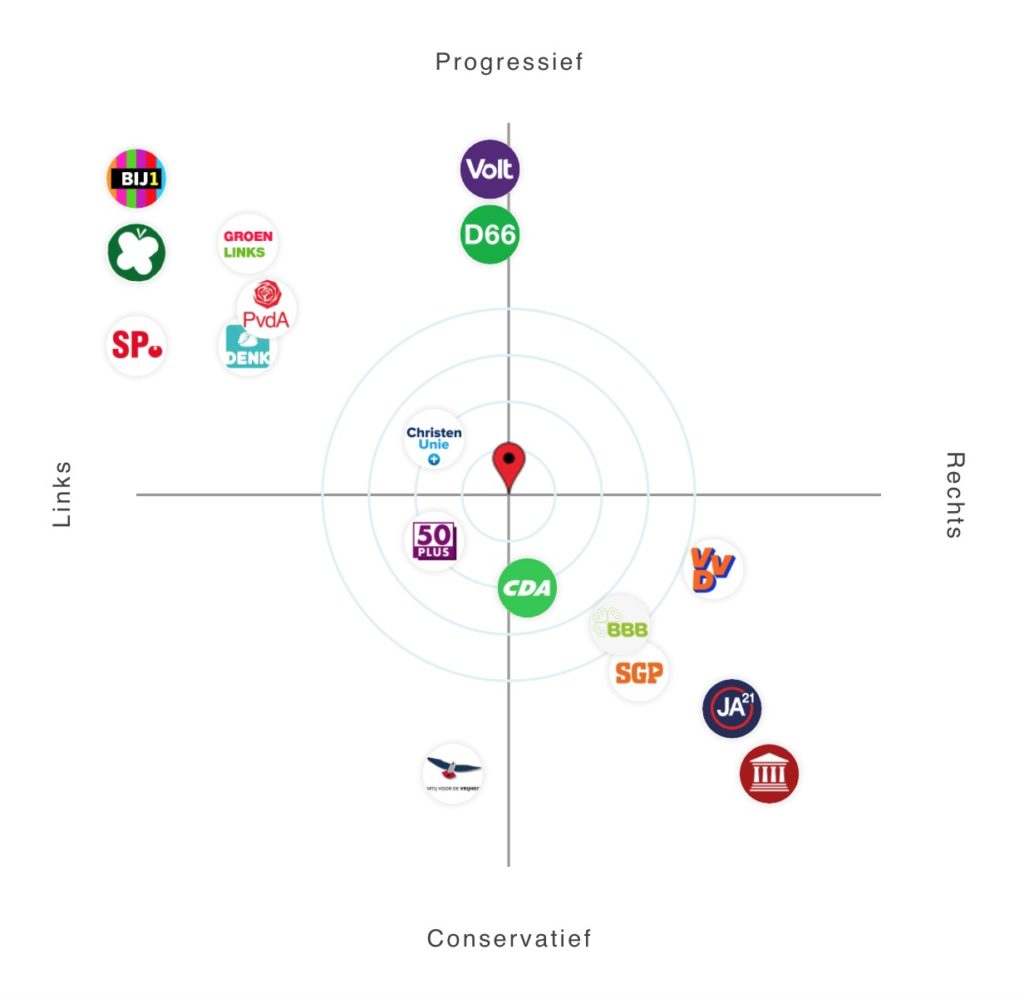

On the left, many voters were seriously doubting which party would be able to make the next government tilt to the left. In the 2017 elections, the combined left had lost a net of 20 seats, with Jesse Klaver’s GreenLeft (GroenLinks) emerging as the largest left-wing party. However, he was unable or unwilling to enter government and after a complex coalition formation, Klaver ended up in the opposition benches. The more pragmatic left-wing voters were hesitant to again support GroenLinks, yet also the Socialist Party (SP) with their relatively new leader Lilian Marijnissen (daughter of a previous leader, Jan Marijnissen) did not look like gaining any steam to threaten the dominance of Rutte. As neither SP, nor PvdA nor GroenLinks seemed a viable alternative to Rutte, D66 leader Kaag openly challenged Rutte for the position of Prime Minister. D66 – a centre-right, progressive party – was part of the incumbent coalition consisting also of Rutte’s own VVD, CDA and the Orthodox Protestant Christian Union (CU). For many voters on the left, the only viable option to tilt the next coalition to the left was to vote D66, a centre-right, pro-market party (see the political landscape figure).

The campaign thus became dominated by the theme of ‘leadership’, as Rutte emphasised he needed another term to ‘get us all through the pandemic’ and Kaag suggested that she would provide a ‘new leadership’. Despite all the hardship caused by the lockdown, with many losing their income, job, or company, economic issues were pushed to the background.

The issue of leadership, particularly with regard to the handling of the pandemic, was exacerbated by the fact that the populist parties attacked Rutte and his ministers for being too heavy-handed, particularly as the government introduced a curfew. The curfew led to violent protests in 11 Dutch cities and put the pandemic even more centre-stage. On the populist wing of the political spectrum, Geert Wilders’ PVV still dominated in the polls, but only because the populist party under the leadership of Baudet, Forum for Democracy (FvD), had collapsed and split over a group of activists that had shared Nazi propaganda, anti-Semitic tropes, and homophobic discourse. The split-off, named The Right Answer 21 (JA21), completed the fragmentation of the populist pole of Dutch politics.

In the regional elections in 2019, Baudet’s Forum party had actually emerged as the largest party in the country, in the same year that the Labour Party had become the largest party in the European elections. This shows that both turnout and volatility among Dutch voters makes significant power shifts possible.

The outcome of the election was a further defeat of the left, losing another net 12 seats, rendering the political left a marginal force at least until the next elections. Many traditional left-wing voters supported D66, which won four seats to become the second-largest party after Rutte’s VVD. The biggest winner, however, was the populist block that gained a net of six seats.

Immediately after the election, Kaag claimed that ‘political moderation’ had won in this election. From two corners of the political spectrum, this analysis will not be shared. People who support populist parties see D66 as an extremist party on issues like climate change, European integration, and multiculturalism. For them, Kaag portraying herself as moderate will sound insane. From the radical left, Rutte’s policies are pro-market and pro-big-business, so that they will also question that moderation has won. At the same time, across the progressive side of the political spectrum from SP, GreenLeft, PvdA to D66, people are really concerned about the ever more openly racist, xenophobic, and conspiratorial rhetoric coming from the populist side and their supporters.

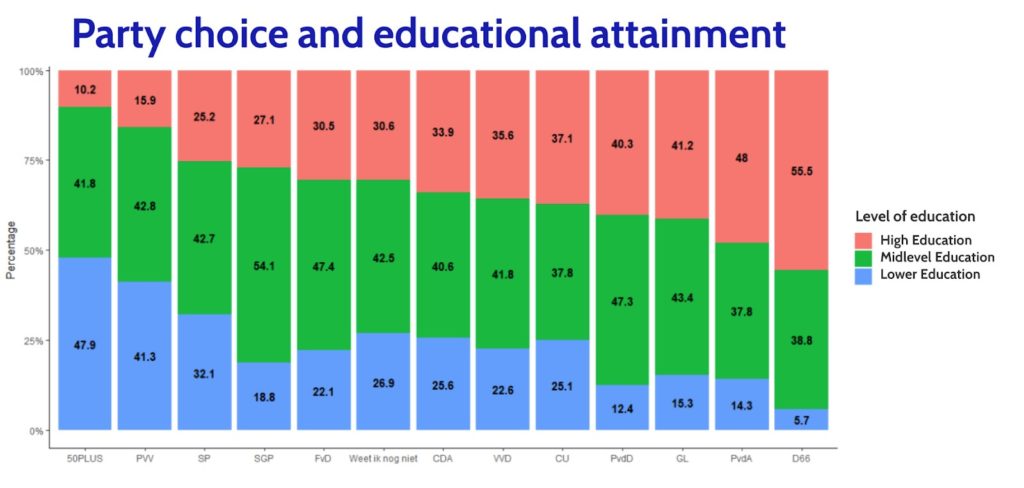

What seems to be occurring more and more is the sorting of voter groups by education. Increasingly the parties on the progressive side attract voters with higher education from more urban communities – or at least the more well-to-do areas in larger cities – while the conservative-nativist pole of the political spectrum represents more people with mid-level and practical or vocational training from suburban and smaller communities. In the figure below we see that in particular D66, PvdA and GreenLeft are the parties of the higher educated with only a marginal segment of voters with lower educational attainment. Note that the left-wing populist SP attracts more voters with practical education and work experience and distinguishes itself from the rest of the left. We see that particularly the PVV attracts more voters with lower educational attainment. Even when we control for age – as older generations did not enjoy the same educational opportunities – this educational divide remains visible. It seems that David Goodhart’s grim tale of the ‘Anywheres’ being politically pitted against the ‘Somewheres’ is becoming a reality in the Netherlands.

Photo Credits: Shutterstock.com/MarcelRommens

Related articles:

Dutch elections 2021: no recovery of Social Democracy!, by Hans Keman.

Last call for the Dutch Left?, by Klara Boonstra.

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-advertisement | 1 year | Set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin, this cookie is used to record the user consent for the cookies in the "Advertisement" category . |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| csrftoken | past | This cookie is associated with Django web development platform for python. Used to help protect the website against Cross-Site Request Forgery attacks |

| JSESSIONID | session | The JSESSIONID cookie is used by New Relic to store a session identifier so that New Relic can monitor session counts for an application. |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| __cf_bm | 30 minutes | This cookie, set by Cloudflare, is used to support Cloudflare Bot Management. |

| S | 1 hour | Used by Yahoo to provide ads, content or analytics. |

| sp_landing | 1 day | The sp_landing is set by Spotify to implement audio content from Spotify on the website and also registers information on user interaction related to the audio content. |

| sp_t | 1 year | The sp_t cookie is set by Spotify to implement audio content from Spotify on the website and also registers information on user interaction related to the audio content. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| CONSENT | 2 years | YouTube sets this cookie via embedded youtube-videos and registers anonymous statistical data. |

| iutk | session | This cookie is used by Issuu analytic system to gather information regarding visitor activity on Issuu products. |

| s_vi | 2 years | An Adobe Analytics cookie that uses a unique visitor ID time/date stamp to identify a unique vistor to the website. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| NID | 6 months | NID cookie, set by Google, is used for advertising purposes; to limit the number of times the user sees an ad, to mute unwanted ads, and to measure the effectiveness of ads. |

| VISITOR_INFO1_LIVE | 5 months 27 days | A cookie set by YouTube to measure bandwidth that determines whether the user gets the new or old player interface. |

| YSC | session | YSC cookie is set by Youtube and is used to track the views of embedded videos on Youtube pages. |

| yt-remote-connected-devices | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt-remote-device-id | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt.innertube::nextId | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

| yt.innertube::requests | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| COMPASS | 1 hour | No description |

| ed3e2e5e5460c5b72cba896c22a5ff98 | session | No description available. |

| loglevel | never | No description available. |