The Progressive Post

Trump’s tariffs can bring a boon for the EU

Amid the shock from Trump’s tariffs, there is a potential for a boon. Yes, tariffs will likely be inflationary for the US and may dampen global economic activity. Yet, the kind of rebalancing of global trade and financial flows that they will cause may turn out to be beneficial, in particular for Europe, if it comes up with a proper policy response.

It is well known that the trade regime that we had so far has produced many distortions in the global economy: some countries are running massive current account surpluses (China and Germany), and others (notably the US) run current account deficits. This means de-industrialisation in the deficit countries and overcapacity in exporting countries. Trump is correctly concerned about this. His method, however, is sub-optimal, to put it mildly. A much better solution would be capital controls on financial flows to the US, which would cause also a rebalancing of trade. However, it is difficult for any US administration to do this, as it would undermine the ‘exorbitant privilege’ of the dollar as a reserve currency. Interestingly, in 2019 two US senators proposed a bill, the Competitive Dollar for Jobs and Prosperity Act, which called for taxes on capital inflows but did not get support at the time. Now these ideas are back on the table. The Trump administration and analytical centres close to it mull an idea of taxes on capital inflows.

The apparent increasing difficulty that the US has in keeping the reserve role for the dollar and supporting its own economy simultaneously points to the need for the reform of the international economic architecture. The idea of an international clearing currency that would help balance the external economic positions of countries, as the ‘bancor’, proposed by John Maynard Keynes in the aftermath of the Second World War, is coming back to the discussion from time to time, especially when fragilities of the international economic architecture are exposed. It got serious attention in the aftermath of the 2008 crisis, when the governor of the Chinese central bank suggested using IMF special drawing rights (SDR) to balance international positions. SDR is an international reserve asset created by the IMF, like the bancor, however it is not currently used for balancing external accounts of countries. That time, however, it was rejected by the US establishment. The destruction of the old trade system by the Trump administration might give a new push for global reform.

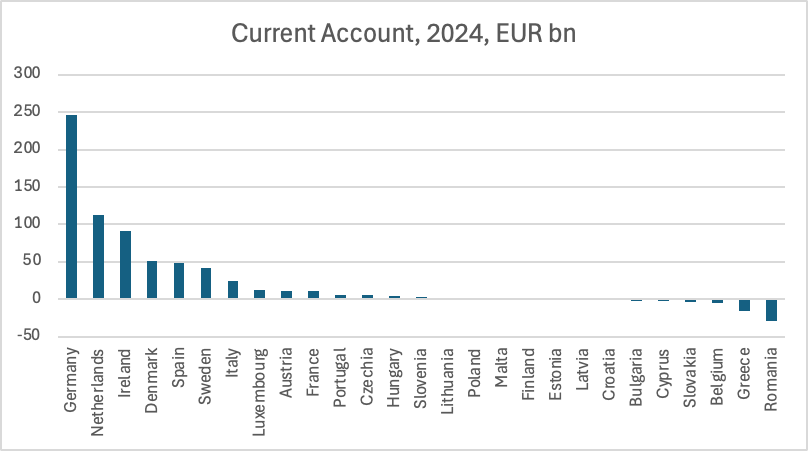

What can the EU do to navigate global rebalancing? The European problem is a lack of internal demand, as evidenced by the massive current account surpluses. Germany is the biggest contributor, followed by the Netherlands and Ireland. Dutch and Irish data, however, are substantially inflated: in the Netherlands, due to the fact that trade is registered at the port of entry, with Dutch ports being the main European ports; and the Irish data is distorted due to tax evasion.

Current account balance in 2024, in billion Euros. Source: Eurostat

The case of German current account (CA) surpluses has been discussed for a long time: the suppression of real wages and low investments lead to a mismatch of supply and demand, with the resulting push to export the excess supply elsewhere. These trade dynamics contributed to the emergence of substantial imbalances within the euro area and the subsequent debt crisis in the Southern EU countries in 2008-2012. After the crisis, when Southern Europe could not absorb German surpluses anymore, they increasingly flowed to the US. With US markets less accessible for the European producers under Trump’s tariffs, the main solution for the EU will be to stimulate internal demand. In their 2020 book ‘Trade Wars Are Class Wars‘ Matthew Klein and Michael Pettis show that the reason why the trade imbalances emerged in the first place is a highly unequal distribution of income and wealth.

Workers in Germany have been consistently underpaid for what they produced over the last decades, while business owners accumulated massive wealth. Due to wage repression, complemented by fiscal austerity, internal demand in Germany was very weak, not enough to absorb the goods produced by the German industry. German businesses offloaded their excess production elsewhere and reinvested their profits abroad. In the meantime, German and other European workers got no upside from this lucrative trade. All in all, the trade regime we had so far did not benefit workers and led to a continuous growth of inequality. The IMF 2019 Country Report on Germany shows that the German CA surplus was driven by corporate savings and that its benefits were very unevenly distributed. Namely, the growing corporate profits associated with globalisation accrued mainly to households at the top of the wealth distribution, among which business ownership is concentrated.

Current account balance and income inequality in Germany in per cent

Source: IMF (2019) Germany: Selected Issues, Country Report No. 19/214, 10 July 2019

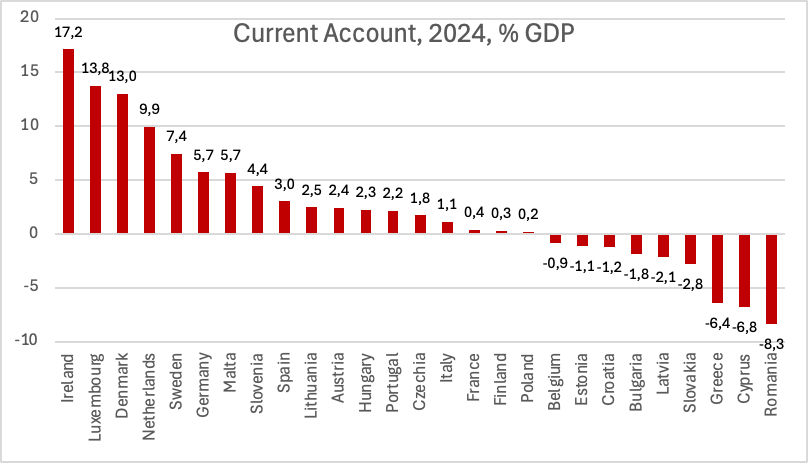

The balancing of external positions is also needed to make the Euro viable. The persistent CA disbalances undermine the single currency as they drive countries apart. A FEPS policy study by Juan Montecino (2022) shows that since adopting the euro , the flow of Northern (mostly German) exports and capital to Southern EU countries led to a substantial appreciation of their real effective exchange rates and undermined their competitiveness. The chart below demonstrates that several EU countries run massive external imbalances.

Current account balance in 2024, as per cent of GDP. Source: Eurostat

This means that a rebalancing of trade and financial flows is also needed for internal reasons of the EU, notably to maintain the coherence of its economy and the euro. In particular, the EU should consider introducing hard constraints on current account imbalances as part of the European semester and possibly ultimately establish a bancor-like system for internal trade flows in the EU. In the meantime, if Europe wants to prevent a recession because of Trump’s tariffs, it needs to spend and invest more. Stronger government spending and investments need to be accompanied by better workers’ remuneration so that they can afford to buy what they produce. The recent monumental shift in Germany in favour of investments is very helpful. This spending increase needs to happen in a way that reduces income and wealth inequality – the main fundamental driver of external imbalances. A range of other structural reforms should accompany this spending: tax reforms to remove advantages for super-rich individuals and large corporations, the development of local economies, more distribution of power toward workers (through employee ownership) etc. This way, the current trade shock may become a boon – if it motivates long-overdue reforms.

Photo credits: Shutterstock AI