The Progressive Post

Regulate, but build too: for a European digital sphere

Europe faces a foundational moment, as it debates how to put the digital transition onto a path that is in the interest of citizens and society. Regulatory efforts focus on reigning in Big Tech, reducing potential harms, and increasing market competition. This is a necessary step. But if Europe wants to develop its own, sovereign vision of the digital space, it needs to do more than just attempt to fix the commercial platforms. It needs to build this space actively, basing it on public interest digital infrastructure. We need a digital public space with democratically governed key services, including social networks and sharing economy platforms, as well as public education, culture and health infrastructures.

The shape of this digital space will largely depend on how data flow through it, and how access and use is ensured in an equitable way. A key policy debate on data governance is now underway, as the European Data Strategy is implemented through two pieces of legislation: the Data Governance Act and the Data Act. Depending on the outcome of this debate, Europe will either develop models for sharing data as a public good, or strengthen a market approach to data that are owned privately and traded as a commodity.

Opening walled gardens: portability and interoperability

With the adoption of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in 2016, the European Union (EU) laid the foundation for a new regime of personal data and privacy protection built around the idea of strong rights for citizens.

Everyone knows the GDPR’s consent mechanisms, but fewer people know the rules on data portability that are included in this regulation. Data portability allows users to take their personal data with them when switching services (eg, you can move all your photos and associated data from Instagram to an alternative photo-based social network). This is an overlooked measure meant to prevent lock-in – not by minimising data use, but by giving users control over how their data are shared.

Unfortunately, users still cannot easily leave services that do not meet their expectations or that they consider harmful. This is partly because of lack of enforcement of data portability. Platforms have strong incentives not to provide all the data they own, and to complicate the portability procedure by design. Facebook will let you download your posts and photographs, but not your contact list or comments. And it will not share the data that it has accumulated about you over time. This makes it hard to use exported data, and even harder to shift to another service, without a sense of having lost some value.

But this is also because of lack of choice. There are simply too few readily available alternatives to the dominant platforms, and there is especially a lack of services that differ fundamentally in how they treat user data, moderate content or generate revenue.

The challenges of the data economy require more than individual choice: they warrant collective responses. An initial step towards this – which is currently included in all major EU legislative proposals – would be to strengthen interoperability rules. Interoperability is a stronger version of portability, a requirement to make data available and allow other services to use them. This sounds technical, but it is a simple principle that can facilitate the development of alternative services using data held by the platform giants. Interoperability would thus contribute to a more decentralised ecosystem of online services that would hopefully be not just useful but also fair to their users.

Yet to achieve this, legislation to reduce the harm of monopolistic platforms and increase competition, for instance via interoperability, will not be enough. Alongside this legislation, Europe also needs to develop a digital environment that is more than a simple marketplace, and that serves society as a whole. Metaphorically, it is not enough to open the walled gardens of commercial platforms – we also need to talk about how the fields around them look. And this space will hopefully be managed as a commons: a resource that is owned and managed collectively, with public interest in mind.

Nurturing a new ecosystem: public infrastructures

In 2020, the EU announced its new data strategy. This is an opportunity that must be seized. As we try to curb the power of commercial platforms, it is through data governance rules that we can support new services and shape a public space. Through legal acts like the Data Governance Act and the Data Act, we can ensure that data are not treated as private property, but as a common good.

In the case of personal data, this requires attention to protecting privacy and other basic rights. But the GDPR shows that protection of personal data can go hand in hand with measures increasing the use of data. And then there are vast pools of non-personal, industry data that can be used to benefit our societies.

A key part of such an ambition must be the willingness to invest in public infrastructures. First, we must consider where there are spaces in our ‘datafied’ societies that are not yet controlled by commercial platforms extracting societal data for commercial benefit. It is in these spaces that Europe needs to build new data regimes. Education is one such space, with the Covid-19 pandemic causing a sudden digital transformation. Or health, where again the pandemic has quickened the development of new platforms for managing our health data, and where there is now a clear vision for sharing medical data in the public interest. These infrastructures should be decentralised and dependent on data sharing between peer services of different sizes, which together form a given ‘data space’. And these spaces should allow for a mix of public, commercial, and civic services

Unfortunately, the European Data Strategy mainly reads as an industrial strategy. The answer to the problems with foreign platforms is thus simply to nurture European commercial champions and hope they will behave differently.

This market focus is typical for European digital policies. Yet the debate on data should not just concern the market, but our societies. And we need to avoid the danger of framing all data as a commodity, through a property right in data. Proposals for such a right have been made before, and are surfacing again. Instead, we should frame the use of data in terms of rights, and focus on ensuring the availability of data – including commercial data – for public interest purposes. The pandemic has shown the value of data-driven health research, and the costs associated with lack of access.

Society-centric data governance

Proper data governance will give us, as societies, means for shaping the digital sphere in the public interest. It will also determine whether new rules for commercial platforms lead to a more varied, competitive, and just digital environment.

This requires the European Data Strategy to centre on principles that are not about market growth but a sustainable and healthy society: supporting the commons, strengthening public institutions, ensuring the sovereignty of individuals and communities, and keeping technological growth and power in hand through decentralisation. We proposed these four principles in our ‘Vision for a Shared Digital Europe‘, which was created by European experts and activists and led by Open Future and the Commons Network.

If we pay attention to these principles, data flows can contribute to an infrastructure that ensures value creation not just in the market, but in a digital public sphere. And hopefully successful platform regulation will also open the Big Tech platforms and ensure that they contribute to a shared data space. To achieve this, the overall vision of a digital public space, fuelled by data flows, is more important than specific data governance laws. Ultimately, we want an internet governed more as a commons, with a greater range of services for the public interest. The different policy reform streams should be connected by a mission of creating a shared ecosystem that is based on strong public infrastructures instead of private control. These will in turn enable the exchange of data and services between public institutions, commons-based projects, individual users and existing (commercial) platforms, on a mutual and non-extractive basis. Such a system would then become an engine for European digital innovation: enabling next generations of services and platforms to emerge, and contributing to a genuinely European technological capacity.

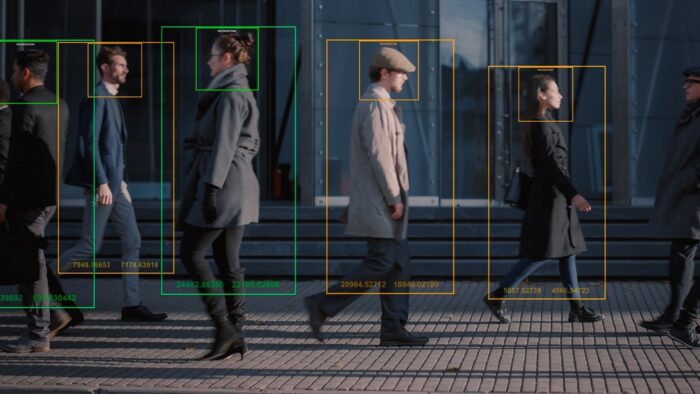

Photo illustration: Shutterstock