The Progressive Post

Unpacking competitiveness

Since Mario Draghi published his report on The future of European competitiveness, its recommendations have been incorporated into the agenda of the European Commission and of member states across Europe. The fresh proposal on the long-term EU budget – the multiannual financial framework (MFF) – has a substantial part dedicated to the ‘competitiveness fund’. Despite such prominence in European policies, the concept of competitiveness, however, remains rather blurred. This is worrying because without clarity of purpose, it is not clear where we will end up.

To begin with, it looks like the choice of the word ‘competitiveness’ had a political reason. From the economic point of view, the usefulness of the word competitiveness to describe a country was discussed and successfully discarded in the 1990s. In his famous article from 1994, ‘Competitiveness: a dangerous obsession‘, Paul Krugman explains that the concept of national competitiveness is elusive. Krugman argued that the ‘competitiveness’ of countries did not depend so much on international factors but rather on domestic ones, mainly productivity growth. In the current debate on competitiveness, economists seem to agree, including the IMF (Fletcher 2025, Kaczmarczyk 2025). It is notable that Draghi himself says from the outset of the report that by competitiveness, he means productivity improvements.

This clarification of definitions is important because, by appealing to a concept that is not clearly defined, politicians can justify any policy. Krugman shrewdly remarked this in his 1994 article as well, saying that politicians use the word ‘competitiveness’ to justify hard choices or to avoid them. The current competitiveness frenzy seems to confirm this diagnosis: there is a pressure to dilute green and labour standards and to consolidate several industries (such as telecoms and banking) – all in the name of competitiveness. It is therefore crucial to put the definitions straight and to call things by their name. Moreover, this vagueness of goals can be very counter-productive, as being embroiled in distractions in the name of competitiveness, the EU may miss what actually matters for its success and well-being.

As there is a general consensus that competitiveness actually means productivity, let’s take a closer look at it. It is generally accepted that a rise in productivity leads to an improvement in standards of living, and therefore, this is considered the path to prosperity. While generally true, this path to prosperity encompasses only one aspect: material well-being. There are many other important aspects of a good life, like good physical and mental health, healthy relationships etc. If we look only at productivity as it is usually measured (output per worker or per hour), we miss entirely all other aspects of wellbeing. Why is this important? Because there is a common habit in economists’ analysis, including that of Draghi, to show how Europe is behind the US on productivity, while completely omitting the quality-of-life indicators. On those indicators, the US is in a really bad shape, with high inequality, depression and shorter expected life. Before making prescriptions for the EU to emulate the US, one needs to ask whether this is indeed the ‘north star’ we want to pursue. ForumDD (2024) elaborates on this further and argues that recommendations of the Draghi report, in some cases, go against the goals and aspirations of European citizens.

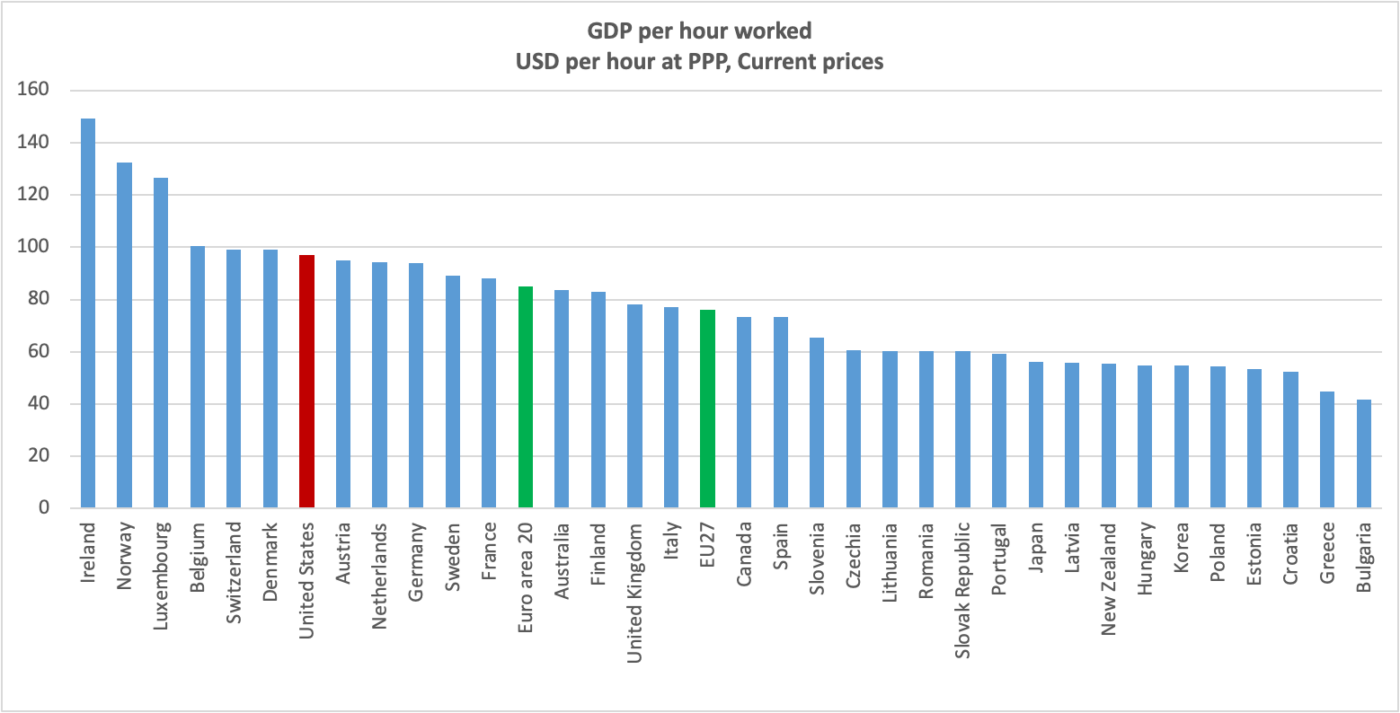

Instead of benchmarking against the US, why not look at other countries that are equally or even more productive but also have good quality-of-life indicators? If we look within the EU itself, it appears that several countries have higher productivity per hour than the US, and some others are very close (see the chart). Why not take Belgium, Denmark, Austria or the Netherlands as a benchmark? Germany’s productivity is very close to that of US as well.

The chart makes it clear that making policy conclusions based on EU averages is quite misleading, as productivity is very much determined by internal factors, and those are different among EU member states.

This chart also highlights the problem with the productivity measure itself: the high output per worker (or per hour) may be a result of many factors that have nothing to do with productivity in the way we intuitively understand. Ireland, for example, has the highest productivity in Europe, largely due to its relatively lax tax regime, which international corporations utilise for profit shifting, resulting in high revenue per hour. Lax tax regimes and high concentration of financial services are ‘helping’ the productivity of Luxembourg and Switzerland.

The choice of productivity measure also matters. If we examine productivity per hour, i.e., output per hour worked, there appears to be no gap in productivity growth compared to the US. Darvas (2023) shows that in terms of output growth, the EU has not fallen significantly behind the US. In fact, it has converged to the US in terms of per-capita output, per-worker output and, especially, output per hour worked.

Additionally, exchange rate fluctuations have a significant impact on cross-country comparisons. Krugman (2025) shows that the increase in the nominal GDP gap between the US and the EU between 2007 and 2024 is a statistical illusion, as it is fully explained by the weakening of the Euro after its abnormal strength just before the financial crisis in 2008. This currency movement obviously affects the productivity measures as well.

This unpacking of ‘competitiveness’ brings us to a conclusion that there is no pervasive productivity gap in Europe vis-a-vis the US, it is more an issue of one particular sector – the digital. This is also what Draghi shows in his report, and it is supported by detailed sectoral calculations by Nikolov et al. (2024). IT services and manufacturing of computers and electronics have been the main contributors to US productivity over the last two decades, while productivity in the rest of the industry stagnated. By contrast, the EU has superior productivity in many industrial sectors.

It is clear that the EU needs to develop its digital sector. The question is how. The high productivity of the US tech sector is derived to a significant extent from the high monopoly rents that platforms and big tech companies are extracting from users. Is this a sign of productivity? Obviously not. The European Union has made its choice on this issue and adopted a whole range of digital sector regulations. In its pursuit of ‘competitiveness’, the EU should not lose sight of its own guiding principles. The way to go is not to emulate the US model, but to build its own digital infrastructure, based on public interest and robust competition. In the meantime, a quick way to improve competitiveness vis-à-vis the US would be to restrict the amount of rent that US digital companies extract from European users – their revenues will fall, and by implication, their ‘productivity’ and ‘competitiveness’.

Another reason not to get too excited about the US digital model is that its innovations are primarily focused on consumer markets rather than industrial sectors. Rotman (2024) argues that for AI and other cutting-edge innovations to translate into broad productivity growth, they must penetrate the entire economy. Currently, this appears to be a challenge in the US, as digital innovators are often disconnected from the industry there. This connection, by contrast, is prevalent in Europe, where the most significant R&D investments are being made in the industry. It may well be that the ‘mid-tech trap’ with predominance of industry-based R&D might turn out to be a boon for Europe, as it enables innovation to benefit the industry.

With this conclusion about the root of ‘competitiveness’ gap in mind, it is worrying to see how different players are driving diverse policy agendas in the name of competitiveness. In particular, this means that the calls for economy-wide simplification/deregulation in the name of competitiveness are not justified. While it is undeniable that the complexity of EU regulations should be reduced, it is not a justification for de facto deregulation. Simplification is a worthy goal, but what the Commission is currently doing is not simplification; it is deregulation. Arnal (2025) notes that the definition of regulatory simplification is lacking in the Commission’s initiatives, leading to confusion between simplification and deregulation. This opacity creates an opportunity for various actors to lobby for deregulation. Arnal (2025) and Pircher (2025) propose a range of ideas on what effective simplification entails.

Technology can also come in handy in reducing the regulatory burden. Why not employ the powerful AI models and other high-tech tools to compile the reports required by regulators? With the use of Web3 Data Space, a new generation internet, this can even be done by government agencies themselves and not by businesses (but for that, businesses would need to give access to their company data). Modern technologies are also capable of collecting data along the value chains, which businesses and policymakers need not just for sustainability reporting but also to monitor the security of supply.

What should the EU aspire to in its economic policies, then? At a high level, the answer can be found in the Treaty of the European Union, which prioritises the well-being of its citizens and environmental sustainability. The European Commission, in its first Von der Leyen mandate, developed a convincing framework called ‘competitive sustainability’. In its Annual Sustainable Growth Strategy 2020 the European Commission stated: “competitive sustainability has always been at the heart of Europe’s social market economy and should remain its guiding principle for the future”. A discussion paper for the Competitiveness Council in December 2020 says “a successful transformation of industry towards a green and digital future will lay the foundation for Europe’s long-term competitiveness”. There is also a vast academic and policy literature underpinning this concept; the most well-known is probably the Competitive Sustainability Index developed by Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership (CISL).

Fast forward to 2024, and the Von der Leyen Commission seems to have forgotten what it said in its first mandate. The Competitiveness Compass that EC presented in January 2025 talks of competitiveness without defining it. In one place, it says that the goal is to preserve production in Europe, in another place, it says that the EU wants to beat international rivals. As already noted, pursuing external competitiveness, which the Compass seems to suggest, is a long-discarded exercise. Moreover, the notion of competition on the global stage and the need to somehow overtake others is depriving the EU of agency. In this kind of framing, the EU is playing a catch-up game where others determine the goals and the rules.

The way out of the shifting and confusing goals is to adopt a long-term and systemic approach to policy-making. Renda (2024) proposes a framework where a stable, long-term goal – a north star – is accompanied by a complex of secondary goals and diverse policy instruments. In this framework, human well-being and planetary sustainability serve as the guiding principles, while competitiveness and productivity are secondary goals, alongside other intermediate objectives.

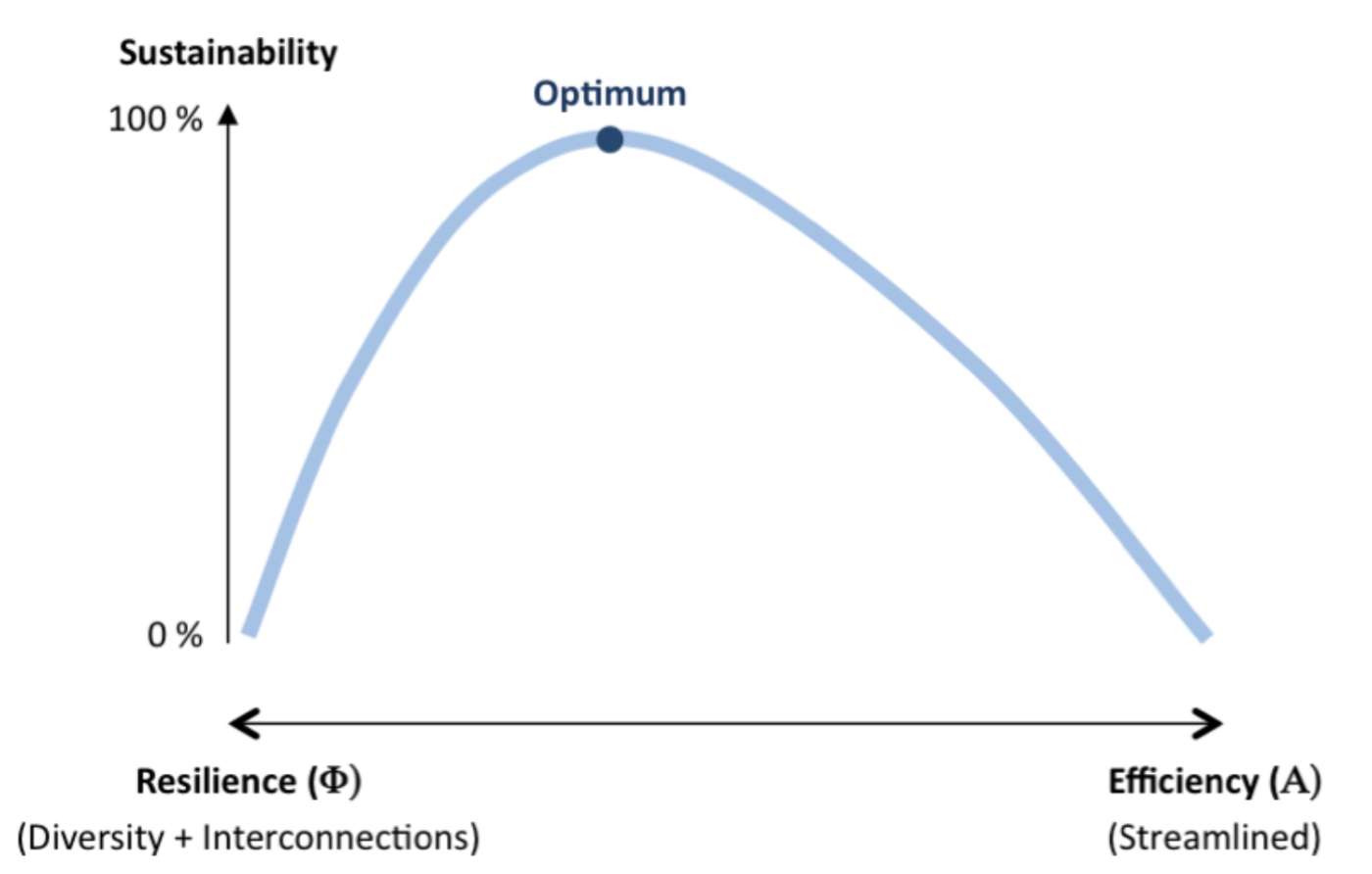

Another important element of the systemic approach to policy-making is the explicit incorporation of risk and uncertainty. This would allow changing the pathway, but not the strategic goal itself. Moreover, striking a balance between risk and efficiency would help maintain a sustainable and balanced economy. In the natural sciences, it is understood that a system is sustainable if it maintains a balance between two opposing qualities: efficiency and resilience (see chart).

Resilience measures a system’s ability to recover from a disturbance or a change in its environment. A system’s resilience is enhanced by higher diversity and by more connections. In general, increasingly efficient systems tend to become more directed, less diverse and, consequently, more fragile.

The excessive focus on efficiency in Western economies in the last several decades led to the emergence of high vulnerabilities, notably in supply chains, that became apparent in the Covid-19 crisis. The necessary rebalancing that we are undergoing now does not mean, however, that the main goal of economic policy should change. What is needed is an explicit incorporation of resilience in policy frameworks. This means moving away from linear policy-making and instead using risk modelling, multiple scenarios, feedback loops and regular policy correction (Renda 2024).

To conclude, the pervasive narrative of competitiveness can be misleading, as it diverts the EU from pursuing its real strategic goals. Notably, the main conclusion of the Draghi report was that Europe lacks investments in marketable innovation. The European Commission made a very selective reading of his report and out of all proposals picked up simplification, which it turned into deregulation. At the same time, other important Draghi proposals, such as a call for common EU debt to enhance European investments, have been ignored.

The unpacking of competitiveness shows that there is no pervasive productivity gap of the EU vis-à-vis the US. The problem lies in the monopoly power of big tech and their rent-seeking business models, which enable them to earn abnormal returns, as reflected in statistics as high ‘productivity’. Europe’s prime task is to disentangle itself from its grip (not only for economic, but also for security reasons) and develop its own high-tech ecosystems and to make sure that innovation permeates the whole economy. All this should happen under a broader policy framework that aims at human wellbeing and environmental sustainability as the main strategic policy goals.

Photo credits: Shutterstock.com/AI generated