The Progressive Post

The Digital Compass 2030: a capital mistake?

The European Commission’s digital strategy, called the Digital Compass 2030, focuses on technology-oriented goals and refers to cloud, chips and ‘unicorns’ (start-ups valued at over 1 billion USD). Although cloud computing and chips have been major innovations and are still innovated incrementally, they both are much more than that: cloud is crucial infrastructure, and chips are an enabler of more and more products. It is therefore in the interest of both businesses and citizens that cloud computing and chips be widely available.

But what about unicorns? These are not a phenomenon of technological innovation, nor even of digital capitalism in a mere technological sense, but a phenomenon of ‘good old’ capitalism gone wild. Indeed, there are currently over 900 unicorns worldwide! That means over 900 companies, each burning at least $1 billion in venture capital. What is more, unicorns are history, as there are already decacorns valued at over $10 billion and even hectocorns valued at more than $100 billion. In total, we are talking about nearly $3,000 billion in these 900+ companies.

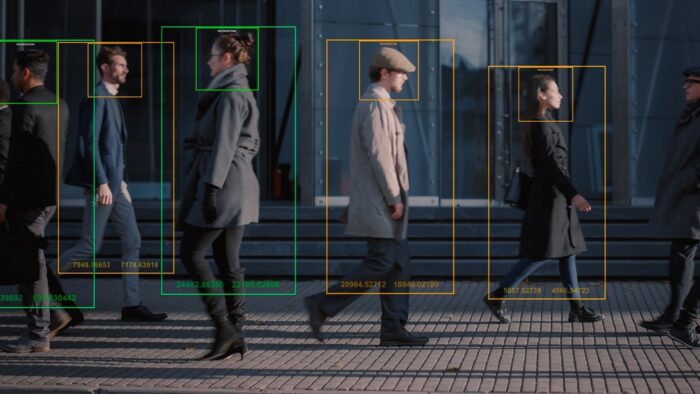

Yet not even 10 per cent of these companies are based in the EU. The crucial question is nevertheless not how we can have more of them in Europe, but why we have allowed a few people to accumulate so much money that they can invest such astonishingly high sums in something that is very often technically not innovative at its core, but ‘just another business model’. Overwhelmingly, the business models of these unicorns focus on what I call distributive forces: ensuring that value is realised in markets. The innovation of unicorns lies not in providing new products or services that meet important social needs or that address pressing problems, like climate change, but it instead lies in these companies’ focus on perfecting sales technique and controlling distribution by achieving significant scale. And all this means helping accumulate even larger amounts of money in even fewer hands. A large amount of artificial intelligence is used, for instance, to nudge consumers into ever more consumption on different online platforms and apps. This simply cannot be in the interest of European citizens.

Will the EU recovery funds – 20 per cent of which is destined for the digital sector – lead to meaningful autonomy?

Over the coming years, the EU will disburse hundreds of billions of euros to be spent on the transformation of the European economy in the wake of the Covid-19 crisis. These funds will be spent at national level, and while the priorities of different national policies may be somewhat varying, ultimately the overall digital strategies at national level are the same everywhere – which is no coincidence because the whisperers from the lobbying organisations and the market-dominating corporations all sit at the crucial transnational political levels. Indeed, Big Tech has actually driven EU lobby spending to an all-time high of €100 million!

To see how this plays out, one only has to look at how the topic of internet-based production (known in Germany as Industry 4.0 at that time) was preconceived at the World Economic Forum (WEF) and then orchestrated as a process by management consultancies into national policy strategies. This behaviour does not resemble that of a democracy acting autonomously in the interest of society. Policy does not therefore reflect the common good either nationally and internationally, but rather the interest of influential economic actors. This is not a conspiracy theory. It is a conspiracy of economic interests ‘in the open’, together with a Stockholm syndrome of the political caste – in other words, politicians who are primarily concerned with the interests of big economic players, not with those of society or, for that matter, with those of local merchants or medium-sized businesses which form the backbone of European economies.

If a national political strategy were seriously to pursue other avenues, it would encounter strong resistance, first verbally, but soon also economically. Imagine the pushback a member state would receive if it explicitly decided not to roll out 5G because it preferred to invest in the construction of social housing, for example, or in better working conditions for care workers, or in the renaturation of monoculture forests.

The importance of control over infrastructure

The key both for the economy, and even more so for society, is infrastructure. It always has been. Those who sell off infrastructure endanger their country’s sovereignty and its strategic ability to act. Indeed, anyone who sells off infrastructure totally undermines democracy. This has been abundantly clear since the onset of Covid-19, but it has actually been happening at the political level for decades – not accidentally, or as an unintended side effect, but as the default policy.

Politicians can now clearly be seen selling off the commons, delivering them into the hands of the market, and thus giving up the levers that ensure the ability to shape the future. This is a decades-long process that will probably only end when all the commons have been sold off. Its absurdity is particularly evident when, for example, there are discussions about separating rail infrastructure from operations, and about transferring them from public ownership to the market. If we then want to create political strategies for sustainable mobility, we find we cannot, because we have given away an essential lever of design.

Even what we now call the internet was once in state hands. However, the dismantling of telecommunications began as early as the 1950s when policymakers around the world started to abandon the politics of public service and to refrain from embedding this critical infrastructure and its democratic control in a way that was oriented towards the common good. These infrastructures must now be painstakingly and belatedly reclaimed.

None of this is a consequence of digital capitalism; in fact, it has made digital capitalism possible. In addition, the platform economy itself acts on the one hand as a parasite of the existing commons, but on the other hand it is racing towards a future in which no social or economic exchange – from logistics to job placement, from mobility to health – will be possible without the use of digital infrastructure. And this infrastructure will be exclusively in private hands, and mostly owned by companies that are headquartered in other national jurisdictions, thus making it impossible for this infrastructure to be reached via regulation at the national or even European level. If we do not stop this process now, we may never be able to regain control.

Conclusion

Belatedly, there are now several policies being formulated that aim to regulate certain tech firms from Silicon Valley (more in California than in Europe). In some ways this is a good thing, although the effort is being made quite late in the day and is too limited. We do not need to regulate a few black sheep – we need to tame the worst sides of today’s capitalism and at the same time develop a policy that dares to think about an economy without growth. A post-growth society is basically incompatible with today’s digital capitalism. The EU talks about sustainability, but digital capitalism is about endless scaling and ubiquitous consumption. The first step to improvement is to acknowledge that we live in a hijacked democracy and that we need to take back control.

Photo credits: Alexander Supertramp/Shutterstock