The Progressive Post

The elephant in the European room

Frontier technologies and emerging industries are increasingly dependent on critical raw materials (CRMs), such as rare earth elements for wind turbines, and lithium and cobalt for batteries. The green and digital transitions of the economy are thus conditioned by access to and control over many CRMs. Recent EU initiatives, such as the Open Strategic Autonomy (OSA) and the Critical Raw Materials Act (CRMA), represent the EU’s strategy to secure a stable supply. However, such a strategy is likely to be over-reliant on domestic potential, applying a top-down approach that risks falling short in addressing key constraints and further weakening the EU’s international standing.

The rapidly growing demand for CRMs exposes high-tech industries and technological advances to intensified supply chain risks, due to factors such as material scarcity, geographical concentration of reserves, trade disruptions and wars, geopolitical instability and resource nationalism. Supply chain resilience through diversification and increasing domestic supply is thus high on the EU agenda, with the EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen periodically announcing new plans to counteract the Union’s vulnerability.

The CRMA sets benchmarks aiming to diversify the EU supply of critical and strategic raw materials by 2030. It introduces specific standards to build European internal capacity and move away from the heavy reliance on extra-EU imports, especially from China. China is the biggest producer of refined materials extracted elsewhere, for the most part in the Global South.

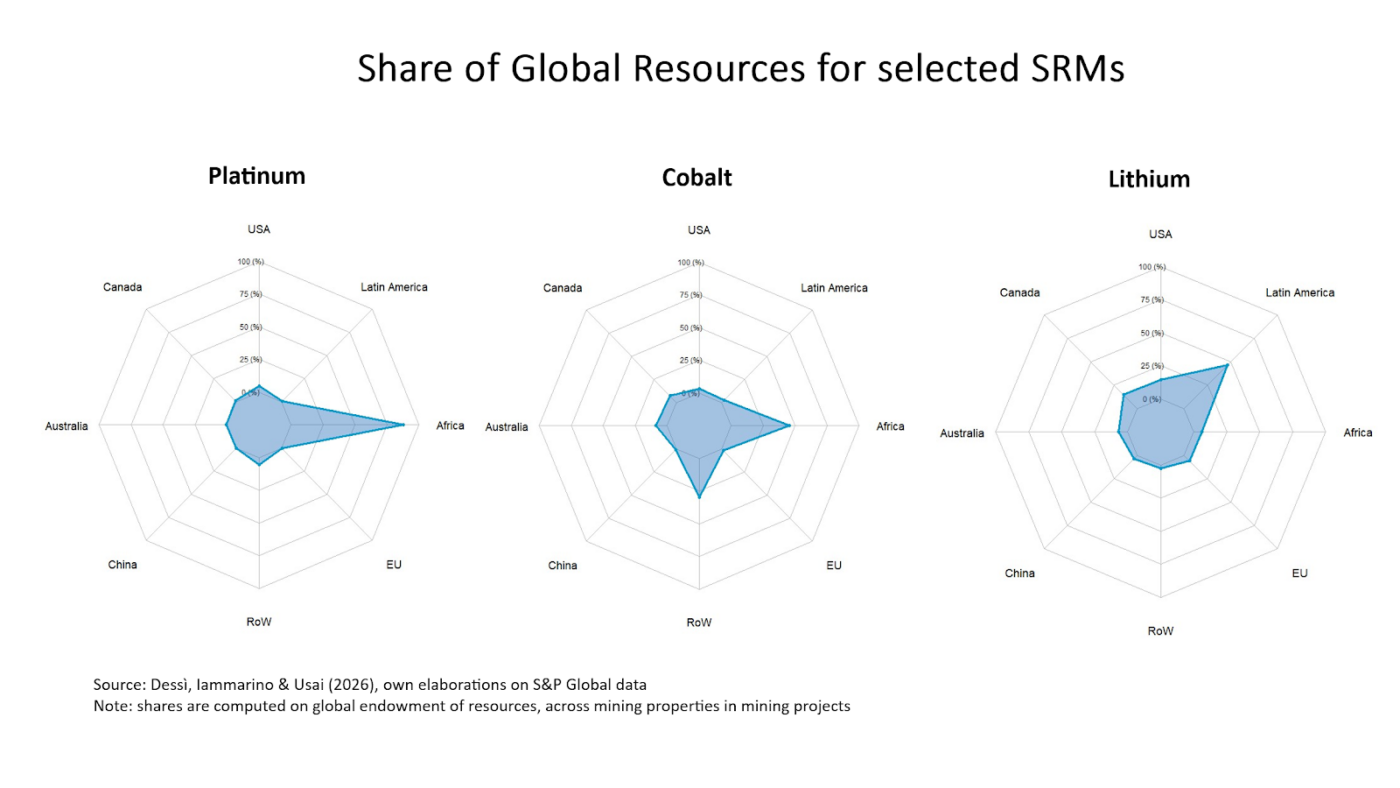

The benchmarks for the EU’s independence goals, however, do not seem to be realistic. The major ambition of increasing European extraction and production of CRMs – set by the CRMA at 10 per cent and 40 per cent of the EU internal consumption, respectively – clashes with significant barriers to its achievement. First, the EU has very limited mineral reserves (e.g. in Fig.1 below), though their assessment is made uncertain by the lack of a complete, harmonised and updated database at the union level. The latter should be the starting point for any evidence-based policy strategy.

Figure 1

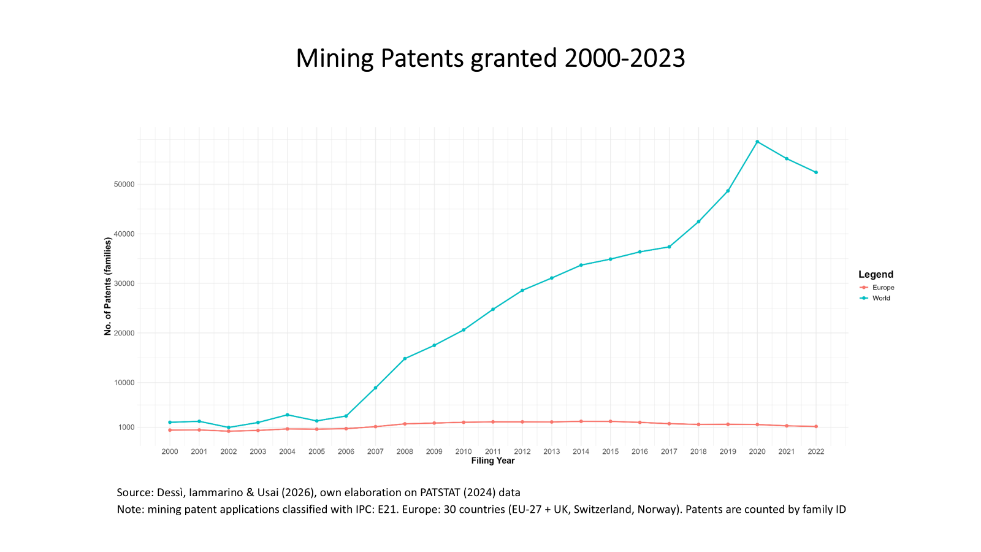

Second, the geological endowment of CRM reserves does not necessarily translate into domestic CRM supply, especially in the short- and medium-term. Mining and industrial production capabilities, especially technological innovation and scale economies in mining, processing, and downstream sectors (such as refining and metallurgical transformation), are paramount, requiring massive long-term investment in high-fixed-cost activities. Mining in Europe has been in retreat for decades, with mining clusters dissolved and a loss of specialisation and expertise at low- and high-skilled levels. The EU’s far more stringent environmental regulations compared to elsewhere require a mining industry capable of operating at the technological frontier. But even here, Europe does not seem to have strong comparative advantages (Fig. 2 below).

Figure 2

Besides these limitations in terms of resource endowments and human capabilities, the CRMA also ignores the serious environmental and social risks associated with pushing up domestic supply. The act aligns with the broader framework of the OSA and its overarching goals of security, competitiveness, and national sovereignty. Yet, natural resources have a distinct geographical footprint, and their extraction entails very high costs in terms of localised emissions, groundwater and soil pollution as well as biodiversity loss. Many of the EU’s regions concerned by mining and prospecting activities have already denied their social license to operate. This outcome was expected, as the European macro-strategies that have global objectives oftentimes overlook their place-specific impact and implications.

These contradictions are internal to the EU. In addition, the excessive emphasis on short-term increases in domestic CRM production goes together with insufficient efforts to ensure resilient and equitable extra-EU supply networks. The CRMA benchmark of importing no more than 65 per cent of the EU’s annual consumption of any specific CRM from a single country has been framed by statements indicating the Union’s willingness to associate only with like-minded countries and to de-risk from China. New forms of dialogue and international collaborations with the Global South and the Other North have been mentioned formally but remain mostly on paper. Europe seems stuck in a global geopolitical vision that resembles the cold-war order. This, added to its never-ending Marshall-plan-syndrome, has prevented any serious commitment to deep reform of the multipolar global governance.

This misalignment has stalled any real progress in cooperation, particularly with the neighbouring African countries and regions that, contrary to the EU, are rich in CRM endowments. The African Union has also adopted its own CRM strategy and priorities. The concept of criticality is considered less in terms of technological sovereignty and more through the lens of local economic development, industrial upgrading, innovation and job opportunities, which can be offered by the growth of downstream material refining and transformation sectors and related technological advances.

Yet, the repeated attempts by the EU and its member states to secure access to raw resources through unbalanced and unfair bilateral agreements follow an extractivist logic that eludes any notion of local content creation. Such a logic fails to confront the typical effects of the resource curse, fuelling corruption, conflict and appropriation of rents by restricted local elites and foreign-controlled mining and financial corporations.

At the same time, in Africa – as well as in Europe – subnational regions are concerned with the environmental impact of foreign-owned multinationals, while local actors and communities demand equity and transparency in sustainable development relationships and strategies. Concerns and efforts related to the sustainable development goals (SDG) and the green transition may be felt differently across different geographical areas, but they could provide a unifying platform for collaboration between EU regions and their counterparts in the Global South.

Europe’s open strategic autonomy should not be conceived as a defensive and selective tool, but as an inclusive policy, open to dialogue with the South and the East of the World. If the EU is truly committed to advancing rapidly in low-carbon technologies, it should do so by investing in materials science and research on recycling and substitution, and by cultivating just partnerships with Africa, Asia and Latin America. Moving beyond accessing raw materials and effectively addressing the trade-offs between technological and environmental objectives, once and for all, is the only way to prevent the elephant crushing the fragile European room.

Photo credits: Shutterstock/mykhailo pavlenko