The Progressive Post

European fiscal rules: reform urgently needed

The EU’s fiscal rules are currently deactivated due to the Covid-19 crisis. However, returning to the pre-Corona rules would be counterproductive. The first priority of reform efforts should be to ensure that applying the rules will not deepen economic crises and hold back recovery. The second priority should be to allow for more public investment.

Budget deficits and public debt ratios have risen massively in all EU countries in the wake of the Covid-19 crisis. The question of how European economic policymakers should deal with this will keep us busy for many years.

The fiscal rules are currently not applied as the general escape clause was activated when the Corona crisis hit. The Commission has recently clarified that the rules should remain suspended for 2022 as well. As an intermediate step, prolonging the deactivation makes sense, as one thing is already clear: a return to applying the EU’s fiscal rules as before the pandemic started would be counterproductive due to the changed realities caused by the crisis. It would force the governments of numerous countries onto an austerity path that undermines economic recovery – and thus also negatively affects debt sustainability. However, simply using the escape clause for another year or two will not be enough, because uncertainty about the future path of fiscal policy for national governments remains as long as effective reform efforts are not undertaken to avoid that applying the rules will hold back recovery from crisis.

If policymakers were to repeat the mistakes they made in the aftermath of the financial crisis – when, from 2010 onwards, excessive fiscal consolidation undermined the economic recovery – the Eurozone would be torn apart in the foreseeable future. Negative domino effects would be all but certain for all member states, including Germany and so-called ‘frugals’, such as Austria and the Netherlands, which rely heavily on export and which, due to their industrial structures, are strongly linked to the other EU member states.

In early 2020, the European Commission initiated a review process for the existing EU governance framework – including the fiscal rules –, but the review was put on hold when the Covid-19 crisis hit. Soon, this discussion on whether and how to reform the rules framework will gain traction again.

However, simply starting by discussing pros and cons of specific reform proposals is potentially misleading. It is necessary to be clear about the main objectives first. What should a reform achieve? What should the main political priorities be? Two objectives should be focussed on when it comes to reforming the EU’s fiscal rules: 1) countering the current pro-cyclical bias and ensuring that all countries can recover swiftly from the crisis, and 2) making space for public-led investment initiatives.

No more pro-cyclical rules

The current fiscal rules are characterised by a pro-cyclical bias, which was particularly clear during the years of fiscal austerity from 2010 onwards. In several member states, applying the fiscal rules has contributed to unnecessarily deepening and prolonging economic downturns, leading to avoidable social hardship. However, the rules have also failed to ensure countercyclical fiscal policies during the ‘good times’ before the financial crisis.

This pro-cyclical bias has triggered unintended political consequences: in several member states, political polarisation has increased in the aftermath of the financial crisis against the background of excessively tight fiscal policies, which have produced rising anti-EU sentiment in several member countries. Strictly applying the EU fiscal rules demands government spending cuts and tax increases from crisis-ridden countries at the wrong time, stifling the economy, holding back recovery and, by consequence, undermining a reduction of crisis-related increases in public-debt-to-GDP ratios via higher economic growth.

Against the background of low interest rates, fiscal policy has become the prime tool for macroeconomic stabilisation. The macroeconomic environment has changed in profound ways, indicated by persistently low inflation and interest rates, and this must be accounted for when thinking about the future fiscal stance in member countries. A main focus of reforming the fiscal rules should be to eliminate the pro-cyclical bias, which has caused large economic and social costs across Europe.

In this context, the technical details of the rules are of high political relevance: cyclically-adjusted fiscal variables – which are based on the idea of correcting headline fiscal balances for the effect of the business cycle on government revenues and spending – are currently crucial for medium-term budgetary objectives of member states. Biases in estimating these cyclically-adjusted fiscal variables have promoted counterproductive pro-cyclical fiscal policies. Whatever the final reforms look like in detail, we urgently need to solve the underlying technical problems, which imply a tendency of revising downwards the fiscal space of member states in times of economic stress.

Making space for public investment initiatives

The second major objective in reforming the EU’s fiscal rules should be to allow for more public investment. This is essential for governments to stabilise the economy in the short, and in the medium run. And it is vital for successfully addressing major long-term challenges such as climate change and digitalisation.

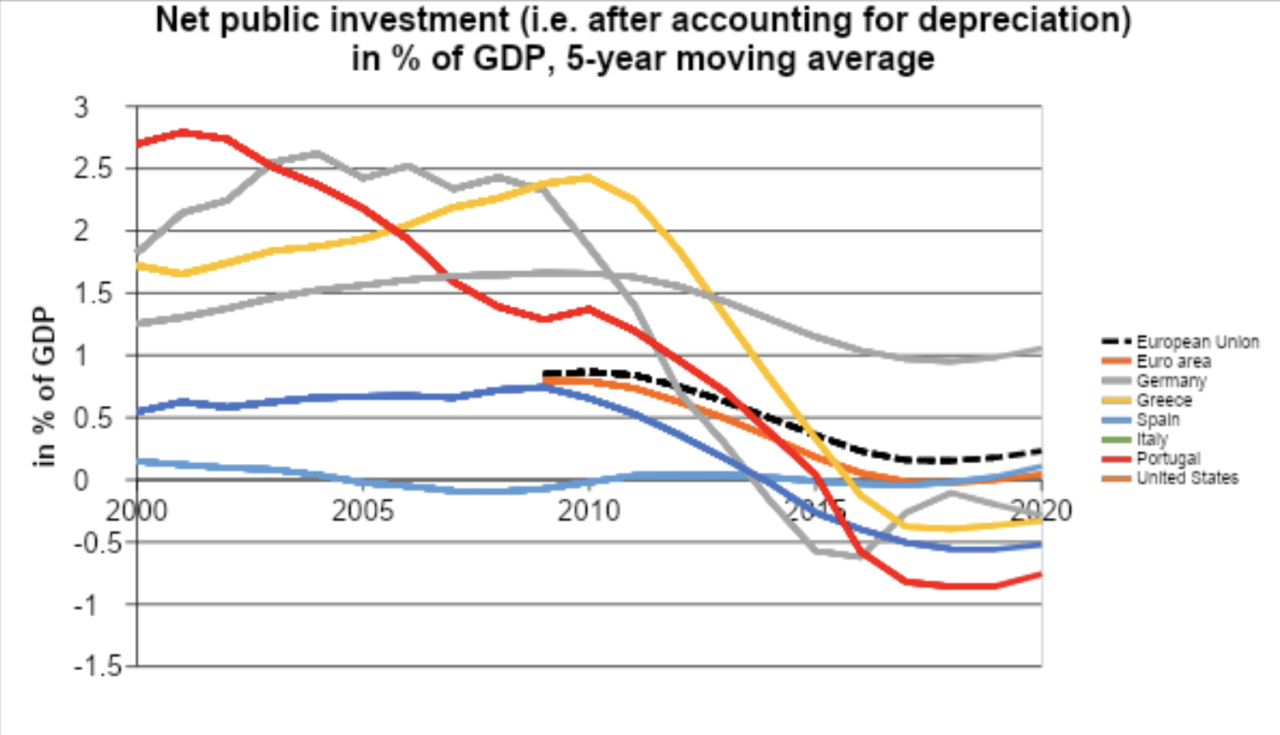

Unfortunately, the current fiscal rules do not adequately distinguish between investment and non-investment spending. Therefore, they have also failed to shield public investment from being cut in times of economic stress. Public investment has fallen drastically over the last decade in many European countries. This is related to the pro-cyclical bias of the fiscal rules described above: governments can quickly cancel investment projects or put them on the back burner as the austerity pressure mounts.

This is exactly what has happened in large parts of the Eurozone over the last ten years. Net public investment (which accounts for depreciation) was negative in the years before the Covid-19 pandemic in large parts of the Eurozone, especially in Southern Europe. This means that the public capital stock has been decaying. Given the large needs for public investment (in areas such as transport, communication networks and decarbonisation) that are still unmet, recent public investment outcomes in Europe are policy disasters with negative consequences in the long run.

If the fiscal rules allowed more public investment, this would, on the one hand, help strengthening the basis for prosperous long-term economic development. On the other hand, implementing the European Commission’s agenda for promoting a “green and digital transformation” requires massive public investment over the decades to come. A reform of the EU budget rules should therefore ensure that relevant public investments can be debt-financed without violating the fiscal rules.

Different proposals on reforming the EU’s fiscal rules should be discussed over the months to come. But the one question that needs to be kept in mind is: how much they contribute to achieving these two major objectives of getting rid of damaging pro-cyclical fiscal policies and allowing for more public investment.

Related articles:

Speeding up the reform of EU fiscal rules – back to work, by Anni Marttinen

Changing the debt rule would miss the point, by David Rinaldi